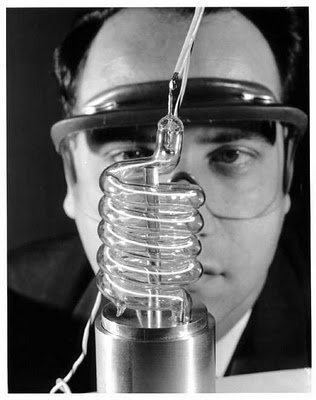

Theodore Maiman made the first laser operate on 16 May 1960 at the Hughes Research Laboratory in California, by shining a high-power flash lamp on a ruby rod with silver-coated surfaces. He promptly submitted a short report of the work to the journal Physical Review Letters, but the editors turned it down. Some have thought this was because the Physical Review had announced that it was receiving too many papers on masers—the longer-wavelength predecessors of the laser—and had announced that any further papers would be turned down. But Simon Pasternack, who was an editor of Physical Review Letters at the time, has said that he turned down this historic paper because Maiman had just published, in June 1960, an article on the excitation of ruby with light, with an examination of the relaxation times between quantum states, and that the new work seemed to be simply more of the same. Pasternack's reaction perhaps reflects the limited understanding at the time of the nature of lasers and their significance. Eager to get his work quickly into publication, Maiman then turned to Nature, usually even more selective than Physical Review Letters, where the paper was better received and published on 6 August.

With official publication of Maiman's first laser under way, the Hughes Research Laboratory made the first public announcement to the news media on 7 July 1960. This created quite a stir, with front-page newspaper discussions of possible death rays, but also some skepticism among scientists, who were not yet able to see the careful and logically complete Nature paper. Another source of doubt came from the fact that Maiman did not report having seen a bright beam of light, which was the expected characteristic of a laser. I myself asked several of the Hughes group whether they had seen a bright beam, which surprisingly they had not. Maiman's experiment was not set up to allow a simple beam to come out of it, but he analyzed the spectrum of light emitted and found a marked narrowing of the range of frequencies that it contained. This was just what had been predicted by the theoretical paper on optical masers (or lasers) by Art Schawlow and myself, and had been seen in the masers that produced the longer-wavelength microwave radiation. This evidence, presented in figure 2 of Maiman's Nature paper, was definite proof of laser action. Shortly afterward, both in Maiman's laboratory at Hughes and in Schawlow's at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, bright red spots from ruby laser beams hitting the laboratory wall were seen and admired.

Maiman's laser had several aspects not considered in our theoretical paper, nor discussed by others before the ruby demonstration. First, Maiman used a pulsed light source, lasting only a few milliseconds, to excite (or "pump") the ruby. The laser thus produced only a short flash of light rather than a continuous wave, but because substantial energy was released during a short time, it provided much more power than had been envisaged in most of the earlier discussions. Before long, a technique known as "Q switching" was introduced at the Hughes Laboratory, shortening the pulse of laser light still further and increasing the instantaneous power to millions of watts and beyond. Lasers now have powers as high as a million billion (1015) watts! The high intensity of pulsed laser light allowed a wide range of new types of experiment, and launched the now-burgeoning field of nonlinear optics. Nonlinear interactions between light and matter allow the frequency of light to be doubled or tripled, so for example an intense red laser can be used to produce green light.

I had a busy job in Washington at the time when various groups were trying to make the earliest lasers. But I was also supervising graduate students at Columbia University who were trying to make continuously pumped infrared lasers. Shortly after the ruby laser came out I advised them to stop this work and instead capitalize on the power of the new ruby laser to do an experiment on two-photon excitation of atoms. This was one of the early experiments in nonlinear optics, and two-photon excitation is now widely used to study atoms and molecules.

Lasers work by adding energy to atoms or molecules, so that there are more in a high-energy ("excited") state than in some lower-energy state; this is known as a "population inversion." When this occurs, light waves passing through the material stimulate more radiation from the excited states than they lose by absorption due to atoms or molecules in the lower state. This "stimulated emission" is the basis of masers (whose name stands for "microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation") and lasers (the same, but for light instead of microwaves).

Before Maiman's paper, ruby had been widely used for masers, which produce waves at microwave frequencies, and had also been considered for lasers producing infrared or visible light waves. But the second surprising feature of Maiman's laser, in addition to the pulsed source, was that he was able to empty the lowest-energy ("ground") state of ruby enough so that stimulated emission could occur from an excited to the ground state. This was unexpected. In fact, Schawlow, who had worked on ruby, had publicly commented that transitions involving the ground state of ruby would not be suitable for lasers because it would be difficult to empty adequately. He recommended a different transition in ruby, which was indeed made to work, but only after Maiman's success. Maiman, who had been carefully studying the relaxation times of excited states of ruby, came to the conclusion that the ground state might be sufficiently emptied by a flash lamp to provide laser action—and it worked.

The ruby laser was used in many early spectacular experiments. One amusing one, in 1969, sent a light beam to the Moon, where it was reflected back from a retro-reflector placed on the Moon's surface by astronauts in the U.S. Apollo program. The round-trip travel time of the pulse provided a measurement of the distance to the Moon. Later, ruby laser beams sent out and received by telescopes measured distances to the Moon with a precision of about three centimeters—a great use of the ruby laser's short pulses.

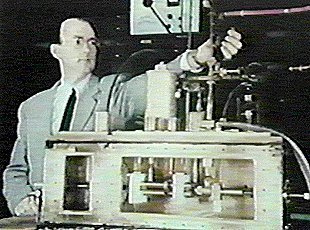

When the first laser appeared, scientists and engineers were not really prepared for it. Many people said to me—partly as a joke but also as a challenge—that the laser was "a solution looking for a problem." But by bringing together optics and electronics, lasers opened up vast new fields of science and technology. And many different laser types and applications came along quite soon. At IBM's research laboratories in Yorktown Heights, New York, Peter Sorokin and Mirek Stevenson demonstrated two lasers that used techniques similar to Maiman's but with calcium fluoride, instead of ruby, as the lasing substance. Following that—and still in 1960—was the very important helium-neon laser of Ali Javan, William Bennett, and Donald Herriott at Bell Laboratories. This produced continuous radiation at low power but with a very pure frequency and the narrowest possible beam. Then came semiconductor lasers, first made to operate in 1962 by Robert Hall and his associates at the General Electric laboratories in Schenectady, New York. Semiconductor lasers now involve many different materials and forms, can be quite small and inexpensive, and are by far the most common type of laser. They are used, for example, in supermarket bar-code readers, in optical-fiber communications, and in laser pointers.

By now, lasers come in countless varieties. They include the "edible" laser, made as a joke by Schawlow out of flavored gelatin (but not in fact eaten because of the dye that was used to color it), and its companion the "drinkable" laser, made of an alcoholic mixture at Eastman Kodak's laboratories in Rochester, New York. Natural lasers have now been found in astronomical objects; for example, infrared light is amplified by carbon dioxide in the atmospheres of Mars and Venus, excited by solar radiation, and intense radiation from stars stimulates laser action in hydrogen atoms in circumstellar gas clouds. This raises the question: why weren't lasers invented long ago, perhaps by 1930 when all the necessary physics was already understood, at least by some people? What other important phenomena are we blindly missing today?

Maiman's paper is so short, and has so many powerful ramifications, that I believe it might be considered the most important per word of any of the wonderful papers in Nature over the past century. Lasers today produce much higher power densities than were previously possible, more precise measurements of distances, gentle ways of picking up and moving small objects such as individual microorganisms, the lowest temperatures ever achieved, new kinds of electronics and optics, and many billions of dollars worth of new industries. The U.S. National Academy of Engineering has chosen the combination of lasers and fiber optics—which has revolutionized communications—as one of the twenty most important engineering developments of the twentieth century. Personally, I am particularly pleased with lasers as invaluable medical tools (for example, in laser eye surgery), and as scientific instruments—I use them now to make observations in astronomy. And there are already at least ten Nobel Prize winners whose work was made possible by lasers.

There have been great and good developments since Ted Maiman, probably a bit desperately, mailed off a short paper on what was then a somewhat obscure subject, hoping to get it published quickly in Nature. Fortunately, Nature's editors accepted it, and the rest is history.

No comments:

Post a Comment